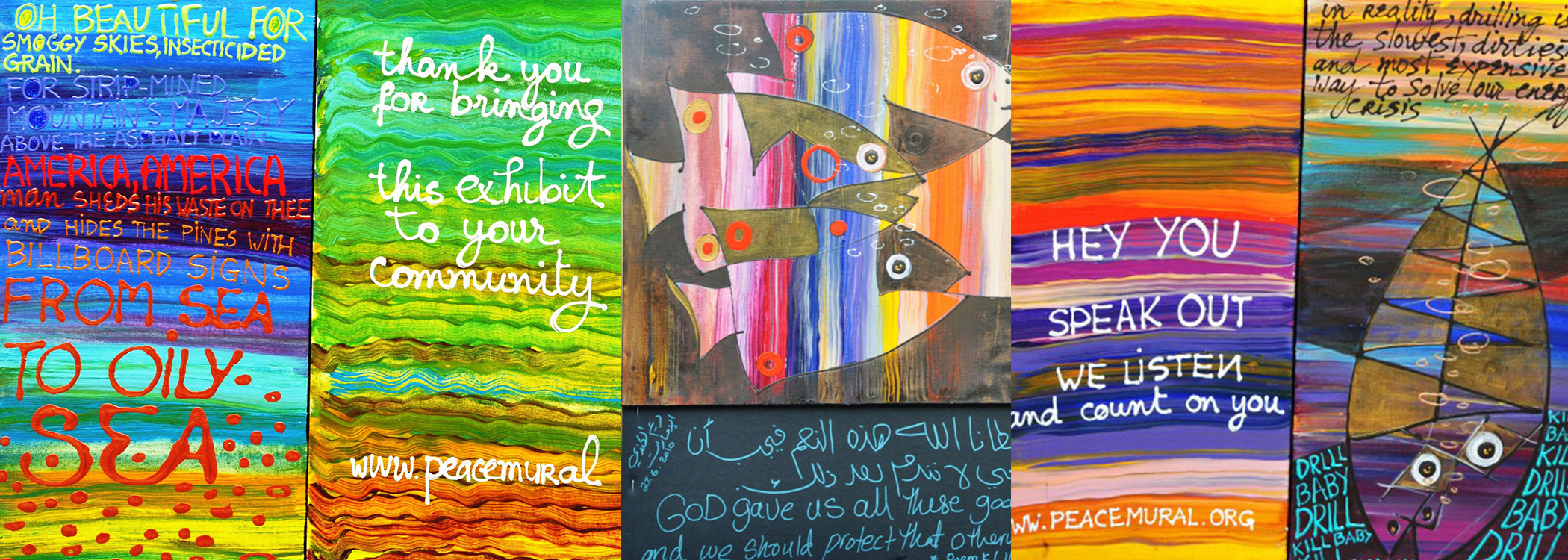

Hundreds of vibrant panels, contrasting in color and varying in size, collectively comprise a 300-foot long mural. Among the most striking images are giant oil-covered pelicans and helpless fish dying in their contaminated environment. Alongside these paintings are passionate hand-written messages that evoke both curiosity and sympathy. Together, the messages tell a story of corporate irresponsibility, environmental devastation, and a vital need for sustainability. “I am mourning the gulf and pray this is not the beginning of the end,” reads one. Another person has written, “For 200 years we’ve been conquering the nature. Now we are beating it to death.”

These words appear amid a variety of other voices condemning, lamenting, or downplaying the BP oil spill and the devastation of the Gulf Coast. Together, these diverse messages capture the current discourse of our nation and the various concerns and opinions held by all sides of the political spectrum. They were compiled by Huong, a self-taught mural artist and lifelong peace activist. Originally a journalist in Vietnam, Huong came to the United States in 1975 as a war refugee. Now, she uses art as a form of personal protest and also as a medium to disseminate her message of peace.

At the end of June, the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington D.C. displayed sections of the Obama Peace Mural, an on-going, 300-foot long demonstration of peace painted by Huong with the assistance of her guest artists and interns Johab Silva, Kyle Mickalowski, Mang and Raymond Lopez. The exhibit featured her new and provocative section, Bleeding in the Gulf, Summer 2010, where Huong captures the voices and values of our nation through artistic representations of the BP oil spill. The mural contains hundreds of original panels, all mostly oil and acrylic on canvas.

During a brief interview, Huong told me that her goal is to paint history as it happens. When the magnitude 7.0 earthquake tore through Haiti on January 12, 2010, Huong started painting that very evening. A week after oil started leaking into the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010, she began working on a new section of the mural dedicated to the disaster. Huong’s remarkable response times to the Haitian earthquake and the BP spill attest to the fact that she works with a passionate sense of urgency.

Words Stand Out

The very nature of Huong’s work opens dialogue between people. Aside from her personal feelings concerning current events, Huong is very eager to incorporate controversial voices, regardless of whether she agrees with them or not. For instance, one panel displays Sarah Palin’s rally slogan, “Drill here, drill now.” A voice from a neighboring panel asks, “Why did it take Obama 13 days to show up in Louisiana?” A third panel has no words — Huong has painted a single fish, swimming in blotches of black and red, blending into its environment, its eyes wide, its mouth gaping.

“Fish are the number-one victims” of the oil spill, Huong said, “but they have no voice.” Such panels are strategically placed alongside quotes and slogans to illustrate nature’s silent suffering. On one particular panel, Huong depicts a group of oil-covered pelicans painted in the same fiery tones as the dying fish. The text below the image — “may God help us” — reinforces their distress.

“Can you imagine all this destruction comes from one well? If oil companies cannot stop the leak, they must stop drilling,” says Huong when discussing her personal views regarding the oil spill. America’s next step, she maintains, should be a personal commitment to change on the individual level: “We must ration our energy use in order to lower demand so oil companies are not pressured to drill more.”

Part of the Whole

Although Bleeding in the Gulf is highly evocative, the exhibit didn’t do justice to the magnitude of Huong’s work. Only one-tenth of the mural was on display at the convention center. The other nine-tenths are still at her studio in Florida. Huong estimates that the entire mural will be around 700 panels. Including the new panels, the entire Peace Mural is about 3,000. The panels will continue to travel throughout the country to cities such as Orlando and Miami, perhaps even returning to D.C. in several months. Currently, Huong is applying for the National Library of Congress to sponsor the Peace Mural to return to the capital on September 25th for the 10th annual National Book Festival.

Huong’s method is bold and poignant. Her murals represent more than just one artist’s personal message; they represent the dialogue, aspirations, and concerns of an entire nation’s unfolding history. The panels depicting Obama’s inauguration capture both the hope for change and the hesitations felt throughout the country. While some panels question the president’s policies and his selection as a Nobel Peace Prize recipient, others express support and encouragement.

The Haitian panels resemble the images of destruction and despair that prompted many humanitarian relief and faith-based organizations to respond to the earthquake. In one, artist Serafema Solokov, under Huong’s instruction, painted a medical official, dressed in white, looking down at a baby cradled in his arms. It is unclear whether the doctor’s grief-stricken expression is due to the fact that the baby is injured, clearly bleeding from the side of his or her head, or because the baby has already died. In another panel, a young woman sits mournfully against a background of rubble.

At the end of our discussion, Huong handed me a marker and asked me to leave a message. On a panel where she had painted a beautiful peace dove, I wrote my message about the transformative power of art. Huong’s art, like the crises that she depicts, require us to participate and not just observe.